Global Vision – Local Execution

How to strategically remove complexity as you scale

- Complexity can arise in any business, no matter the size.

- Understanding why complexity exists can give you a deeper understanding of the problem it was meant to eliminate.

- Don’t eliminate good ideas in an attempt to remove complexity.

- Reducing complexity for frontline workers is a good place to start.

- Executive vision is critical to developing solutions. But to deliver results, front lines must adopt them.

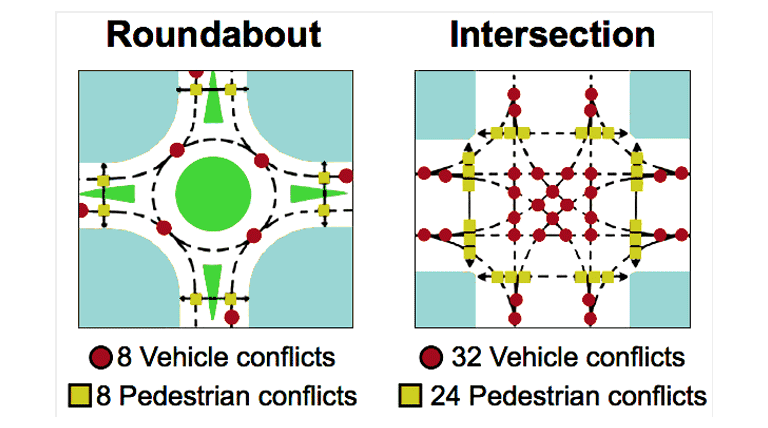

The history of the circular intersection goes back to the 1790s, when it was introduced in the street layout for Washington, D.C.1 Commonly referred to as roundabouts, they feature a one-way traffic pattern moving around a central hub with connecting roads branching out. They were created as a safer, more efficient alternative to traffic signals and stop signs. They remove the complexity of four-way stops and improve traffic flow by keeping traffic moving, particularly in congested areas, as indicated in the diagram below.2

In the 1930s, an attempt was made to improve the traffic circle. Vehicles in the circle now had to yield to those entering the intersection. Rather than improving traffic flow by making it easier for people to enter, it jammed up the flow of traffic quite a bit. Engineers had assumed that as long as they gave cars plenty of room to change lanes, traffic would continue to flow smoothly.1 Unfortunately, that wasn’t the case. Increasing the size of the circle and forcing those already in the circle to react to those trying to enter, added confusion and complexity. Where drivers had once navigated the circle with ease, they now stopped and started to allow other vehicles to enter.

To combat the added complexity, engineers designed bigger and bigger rotaries. This caused even more congestion and led to high crash rates. What once improved traffic flow was now creating more issues than it solved.

Years later, the British experimented with a rule that flipped the previous order of things. No longer did those already in the circle yield to entering vehicles. Instead, it was the job of those entering the circle to yield to the traffic already flowing in it. It was a huge success. It increased intersection capacity and significantly improved delays and crashes.1

The traffic circle was a brilliant invention that helped ease congestion without creating additional problems. But as the circle tried to achieve more, it became more complex and less useful. Rather than throw the concept out entirely, the British were able to refine the model to achieve the desired results.

The United States on the other hand had largely abandoned the traffic circle based on previous results and it was many years before they began to make a comeback.

Similarly, the natural evolution of our business processes creates complexities that can slow us down or even cause an accident. But rather than abandon complexity altogether, we should take a rational view of what’s working and what’s not.

Continuous, thoughtful improvements validated with outcome data can help you remove friction from processes. Doing this systematically can help you avoid destroying good ideas for the sake of removing complexity.

Blind spots in complex processes

Understanding complexity is important because it’s not necessarily the enemy. Complexity can suggest an evolved nuance, depth, consideration, and usefulness.3 Good things. But you only want it where it’s needed. Otherwise, complicated processes just slow things down.

Complexity can arise no matter the size of a business. It can also be managed well no matter the size. What’s important is having awareness, taking stock of what is really happening from the ground level all the way to the executive.

Leaders often cite the manifestations of complexity that they personally experience:

- The number of regions the company operates in

- The number of brands or SKUs they manage

- The number and capability of people on their teams4

While institutional complexity is a legitimate target, it may not always be the best place to start.

For example, you might choose to eliminate a business unit or exit a market to reduce complexity and cost. A big move like that undoubtedly removes complexity but also takes value with it. Instead, concentrating on the friction front line employees and managers experience could be a better place to start. 5

Relatively few leaders consider the forms of individual complexity that most of their employees face.4

- Poorly conceived and confusing processes

- Ambiguous role definitions

- Unclear accountabilities

- Outdated or inadequate tools

These complexities aren’t necessary and don’t add any value to your business. They only make your teams’ work more difficult.

Neglecting them can lead to wasted effort or even organizational damage and can be quite costly.4 McKinsey found that companies reporting low levels of individual complexity had the highest returns on capital employed and invested .5

Being blind to individual complexity could cause too much of a course-correct in your business that actually eliminates a value source.

So, before you begin to try to fix a process, it’s important to understand the nature of the complexity you’re dealing with and why it evolved in the first place. Speak with the team members doing the work every day. They’ll be able to pinpoint the parts of the process that seem overly complicated or time consuming. Just avoid letting small subsets represent the whole. Validate with managers and larger groups of front-line team members to help you shine light on blind spots.4

Global vision, local autonomy

Executive vision and leadership is critical to developing solutions across the enterprise. But to deliver results, you also need to convince those on your front lines to adopt them.

You’ll get a long way just by working with them to understand the problems. (And the people experiencing the friction usually have great ideas for how to fix them!)

Another key to buy-in is accounting for necessary variation. As you create or adapt processes to overcome challenges across large groups or geographies, be sure to leave room for local flexibility.

There are the “must do” procedures, that help you meet corporate safety or quality standards .6 And there are localized needs to meet regulatory, cultural, or technological requirements.

Creating room in your framework for local autonomy will help you meet local requirements while fostering creativity, problem-solving, and flexibility. This increases job satisfaction, performance, and customer service by allowing team members to address needs in real time.6

Standard work procedures help people do their jobs consistently and reliably. Removing individual complexity will improve how quickly and efficiently they do it, while freeing them up to be innovative.

Just be sure that the tools you use to implement standard work don’t create their own complexity. Following global standards and local standards needs to be seamless for the front-line employee.

Accelerating the global vision by removing front-line friction

Our client, a global fortune 100 company, expanded rapidly over several years of M&A activity. Operational efficiency became a major focus for recognizing the value of their scale, and a vision was developed to optimize production across hundreds of global plants.

Company leaders devised standards for productivity, waste, safety, and other critical metrics. They provided these as guidelines for each region to meet and provided tools and techniques to deploy them.

At first, the company tried to deploy standards on paper. Standards specialists would review the upcoming production schedule and print out the relevant SOPs. These would be distributed to line managers and eventually individual contributors.

Team members were instructed to use the paper SOPs to mark their tasks as they completed them. Some followed them to the letter. Others skipped steps or just pencil-whipped the list at the end of a shift. The line managers would then collect the papers and pass them back to the standards specialists. It was a long, time-consuming process, and it still wasn’t clear if everyone was following the SOPs.

There was no correlation between individual contribution and production targets. Without accountability, it was difficult to identify what processes to improve or what team members might need more training to meet their goals faster. This wouldn’t scale.

Abandoning the SOP standards altogether wasn’t an option. Instead, executives managing the project focused on the labor-intensive paper aspect of the process. Converting the paper SOPs into digital documents in Acadia removed thousands of hours of extra work and introduced a new level of accountability for frontline teams. SOPs are delivered and tracked automatically. It’s clear who’s using them and who’s taking shortcuts.

Removing the friction on the front line and tracking SOPs digitally, the company was able to establish a direct correlation between SOP compliance and Gross Line Yield (GLY). After proving it out at one plant, leaders took the program global. In each new plant where standard SOPs were deployed with Acadia, the company beat its GLY goals within the first six months.

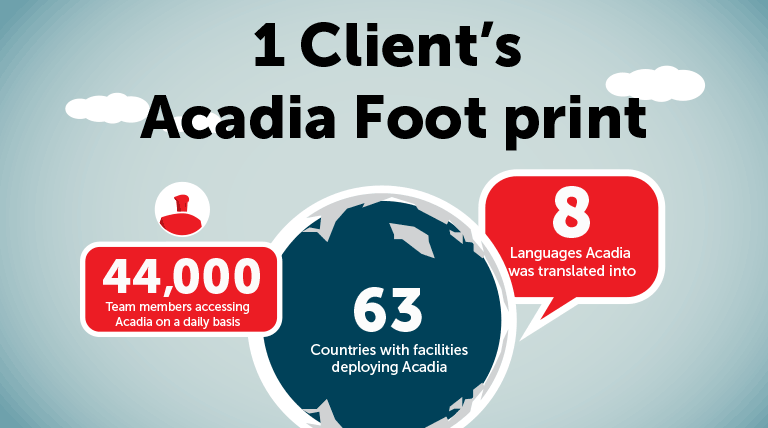

Today, nearly 45,000 team members log into Acadia every day from 63 countries to access digital work instructions, reaction plans, and other critical knowledge that guides their activities.

Overcoming local obstacles

The company saw tangible results as digital SOPs gained traction in plant after plant. But there were still local obstacles to overcome. Executives leading the charge on global standards learned that their ability to transform global results was only as good as their ability to simplify execution based on local restrictions and norms.

Some obstacles were easy to tackle. Acadia has built-in translation tools that can automatically convert any existing content into any language in the world. The content is then entered into workflow for a native speaker to review before becoming available to other employees.

Translation was critical for removing friction as the system was introduced to new countries. It also became helpful for removing friction in countries where multiple languages are common like Canada, Belgium, and the US. Rather than forcing non-native speakers to struggle with work instructions in another language, the company could deploy different languages within the same facility.

Because of the close partnership we formed with our client, we were able to support them when more challenging obstacles cropped up as well. For example, when deploying Acadia in Germany, national trade unions required new functionality to be developed to ensure regional privacy laws could be enforced.

We’ve also integrated Acadia with multiple digital platforms used across the enterprise to help further streamline production for front line teams.

- Multiple company HCM systems allow employees to access Acadia seamlessly while they work

- The company’s ERP and MES systems trigger and assign procedures in Acadia on regularly recurring intervals

- Home grown systems built by the client to deliver work instructions and track skills have been replaced or integrated to remove redundancy

- Data warehouse tools that enable the client to correlate operational data with employee activity data

Over the years, we’ve collaborated with our client to remove other obstacles as they’ve arisen. Good communication from front line team members across the enterprise surfaces process improvements and improvements to the Acadia platform.

Local results roll up to global success

The more employees, business units, and geographies our client has added to Acadia, the more insight they’ve gained to improve operational results.

Facilities and teams that perform above average can quickly and easily share processes with others doing similar work. Individual contributors recommend seemingly minor process improvements that balloon rapidly when shared across the entire organization.

Data integrations that overlay employee activities with production, quality, and safety data help to drive decisions to change processes and train team members at a larger scale and faster pace than was previously possible.

In this way, the company has extracted millions of dollars in savings from procedures they run every day.

Implementing your vision

Most of our clients started working with us in a single team or location then rapidly expanded based on the results they achieved.

We’ve met their pace by deploying Acadia in a highly flexible cloud environment that is replicated across multiple regions for consistent performance and disaster recovery. Today, Acadia delivers 350,000 documents to 255,000 users around the globe.

If you’re tasked with taking your vision globally, you might find it helps to test your assumptions locally first.

Identify a facility or functional team that’s struggling or performing below average. That will help you determine if your solution will work even in the most challenging circumstances.

Establish the baseline metrics you want to improve. Then identify the processes that are being used to do the work. Talk to the teams and find out what they think could improve their performance.

Update the processes based on what you find and deploy them in a system of record that can track execution. In as little as a couple of weeks, you’ll likely see an improvement in your baseline metrics.

Make some additional changes and account for local variations. When you’ve hit a steady state with your pilot program, you can confidently repeat the process with other teams and in other regions.

If you’re looking for a place to start, let’s talk. We’ve helped several clients starting similar projects to make rapid progress toward their goals.

Sources:

Ready to crush your goals?

"*" indicates required fields